(Photo courtesy of hubertbrooks.com)

Political History

The political history of wine in Bordeaux explains in part why the appellations of Southwest France’s “high country” are hidden in its popular shadow. At times called Gascogne (including Béarn) and Aquitaine, today Southwest France is called l’Occitainie administratively.

Bordeaux was controlled by England from 1154 to 1453. This period proved to be a golden era for wine exports to England, Scandinavia, and Baltic ports, laying the foundation for Bordeaux’s enduring reputation as a preeminent source of fine wine. Because Bordeaux merchants controlled access to the sea and collected taxes for the English Kings, a system of market control emerged called Police des Vins or the Privilege de Bordeaux. Here’s how it worked: only new wine from Bordeaux could be shipped before December 1 each year. Even if “high country” wines arrived in Bordeaux in December, they could not be shipped until after Christmas. This prejudiced system remained in place well into the 17th century.

Regional nuances explain modern circumstances in some of the better-known areas of Southwest France. For example:

Only Bergerac was exempt from the Privilege de Bordeaux system. Bergerac became part of British Aquitaine in 1255 and was afforded the same shipping privileges as Bordeaux, thus enjoying the benefits of this golden era, especially shipping to Holland where the Dutch were particularly fond of sweet wines. But disparities existed nonetheless. Bergerac is in a different department than Bordeaux (Dordogne vs. Gironde), resulting in lower bulk prices for Bergerac’s wines. Its image suffers even today in comparison to Bordeaux.

The wine-related histories of Cahors and Gaillac go back to Roman times. Madiran’s foray into wine started later, when Benedictine monks arrived in the 12th century to found the Madiran priory.

Archeological evidence (amphorae) shows that Gaillac was a major wine production center as early as the first century. At the time of the Roman conquest of Gaul, it was one of the first places soldiers came to as they made their way north. (Neither Burgundy nor Bordeaux had yet become significant key wine regions.) They may have viewed Gaillac as the furthest north horizon for viticulture due to its positioning on a navigable river (Tarn). Wines from Gaillac emerge over the centuries in stories of gifts among royals and the court’s preferred libation.

Cahors was the place where Romans crossed the Lot River as they worked their way north. Vineyards were planted early and extensively in Cahors. The town was quite prosperous and cultured even before Bordeaux began to occupy that esteemed position. In fact, half of the wine shipped out of Bordeaux in the 14th century came from Cahors. Despite economic disadvantages caused by the Privilege de Bordeaux, and other setbacks through the 19th century, Cahors managed to maintain its reputation for fine wines. Problems began to escalate in the mid-1800s, however, and for the next 100 years (through the 1950s), Cahors experienced a sharp decline in production and market reputation. Today, producers are aligned in a rebranding strategy to reposition the region as home to “The Original Malbec” in a friendly competition with Argentina.

Madiran wines did not enjoy the export notoriety of the other regions of Southwest France. The Adour River, key to moving product from the region to export markets, did not become navigable until the 18th century, and then only in one small area. Madiran’s rural location in the “middle of nowhere” with no major cities or towns has meant that other crops such as cereals and root vegetables predominate. Most of the great winegrowing sites in the region have already been planted. The wine industry in Madiran seems destined to remain small, slow and steady.

Spiritual Home of Malbec and Tannat Grapes

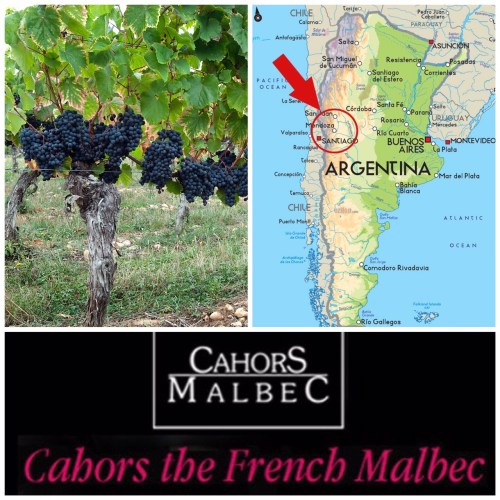

Most wine consumers today highly associate Malbec with Argentina. Others may think of Malbec primarily as a blending partner with the major grapes in Bordeaux blends. One of many French paradoxes, however, is that Malbec’s original spiritual home is actually Cahors.

How can two countries, one in the old world and one in the new, both lay claim to the preeminence of one grape? The history of the Cahors region shows that Malbec has been documented to Roman times, but a combination of market forces and vine diseases diminished growing, production and market relevance.

(Photo credits: Wine Folly grapevine; Wines of Argentina map; Lot Cycling Holidays “Cahors Malbec”)

As this was happening, mostly in the mid-19th century, Malbec made its way to Argentina – according to “Wine Grapes,” possibly via cuttings that were imported to Chile from Bordeaux. The timing is key here: these vine cuttings escaped the deadly phylloxera louse taking hold in France! Malbec quickly found its happy place in the Lujan de Cuyo region just south of Mendoza.

Both Cahors and Argentina have made the modern mistake of either replanting sick vineyards (Cahors) or grubbing up Malbec vines (both countries) in favor of more popular international varieties. It has taken some time to restore total Malbec vine supply in both places. Today about 70% of all Malbec is grown in Argentina, perhaps at least partially explaining consumer familiarity. At considerable risk of oversimplification, differences in terroir yield Malbecs in Argentina that tend to be higher in alcohol and fruit-forward, whereas the Malbecs of Cahors are more savory, even meaty, with firm tannins.

It wasn’t until Cahors AOC was approved in 1971 as a 100% red appellation that the region embarked on a three-decade “golden age.” There has been a strong brand strategy movement afoot for nearly a decade to reposition Cahors as home to the original Malbec. “The French Malbec” campaign was born to elevate Malbec and Cahors to “the center of the modern world.”

Tannat is a dark-colored red grape, richly textured with readily extracted tannins, and relatively high in acidity. But there is one common misunderstanding, oft-repeated by wine writers (and even some wineries on their websites): Tannat is not a thick-skinned grape! Like its brethren great grapes – Pinot Noir, Nebbiolo, and Grenache, just to name a few – Tannat has thin skin, but excellent skin-to-pulp ratio, and thus generates excellent tannins for structure and aging potential.

(Photo Credit: aquitaineonline.com)

An emerging view of Tannat’s health properties is that it has the greatest concentration of procyanidins among common red grapes. This is not the same thing as resveratrol (a polyphenol, or antioxidant). It’s even better. Cardiovascular research conducted by Dr. Roger Corder, author of “The Red Wine Diet” (2006), has found procyanadins to be the main source of red wine’s health benefits. Offered as evidence is the surprisingly long lifespan of people living in the département of Gers in Southwest France where Madiran, home of Tannat, is located. This is the real French paradox!

Less well known in wine world is the fact that, like Malbec, Tannat also has two spiritual homes: Madiran and Uruguay. Wine write Alder Yarrow (vinography.com) describes Uruguay as a “quiet neighbor” to South America’s big producers: Argentina, Chile and Brazil. Uruguay has been producing wine for over a century, and getting to a pretty high level of quality in the last 25-30 years. Many of Uruguay’s residents are Italian immigrants – a longer story for another day. Their native grapes did not do well in the windy, humid Uruguayan climate. In 1870, a Basque immigrant by the name of Pascal Harriague brought Tannat plantings to Uruguay. Today, Tannat plantings represents about 25% of all vineyard acreage.

Traditional Food

Southwest France is the land of geese and ducks prepared every way imaginable (including pâté, foie gras, and rillettes). Fat from these birds is used in many recipes ranging from potatoes to confit. But don’t overlook the many other regional specialties including garlic soup, black Périgord truffles, goat cheeses, walnuts, and dried fruits (especially prunes). The Southwest diet, plus all that tannic red wine, is actually a very healthy one – the real French paradox!!

“Perhaps there is no dish in the Southwest France more iconic, cherished, and controversial than the cassoulet. Cassoulet was originally a food of peasants–a simple assemblage of what ingredients were available: white beans with pork, sausage, duck confit, gizzards, cooked together for a long time.” [dartagnan.com, a French purveyor of gourmet food]

The legend of cassoulet is claimed by Castelnaudary, dating back to 1355 during the Hundred Years War when hungry townspeople gathered up available ingredients to make a hearty stew. Other cities – particularly Toulouse and Carcassonne – also lay claim to this traditional dish as the one, true Cassoulet. The name cassoulet comes from the word cassole, the traditional clay pot in which it is cooked (c. 1377).

(Photo Credit: Curtis Stone on Pinterest)

Traditional cassoulet is made with goose or duck confit, but the recipe varies from town to town in Southwest France. Some recipes include pork shoulder and sausage or mutton. Whether or not to add crumbs to the top is a matter of fierce debate. Even the type of bean is debated. In southern areas closest to the the Pyrénées Mountains, the bean must be the Coco, or Tarbais, bean. Further north, flageolet beans are used. In the spring, fresh fava beans are used. But in other parts of the world, cassoulet is typically made with Great Northern or Cannellini beans.

Some general advice for making a classic cassoulet:

- The texture should be similar to a thick stew. If it is too dry, add some liquid. If it is too moist, cut the crust to concentrate the juices.

- If adapting a recipe to maximize flavor, which is encouraged, use as many different confit meats as possible.

- Always eat cassoulet very hot!

- Cassoulet is better the next day as a leftover after the flavors have had more time to meld.

“How to Make Cassoulet” from allrecipes.com

INGREDIENTS (8 servings)

Beans

1 pound dried Great Northern or Cannellini beans

1 whole clove

1/2 onion

4 cloves garlic, smashed

1 bay leaf

1 teaspoon dried thyme

1/2 teaspoon dried rosemary

10 cups water

Soak Great Northern (or Cannellini) beans in water in a large bowl overnight. Drain beans and place into a large soup pot. Push whole clove garlic into the 1/2 onion and add to beans; stir in 4 cloves smashed garlic, bay leaf, thyme, rosemary, and 10 cups water. Bring beans to a simmer and cook over medium-low heat until beans have started to soften, about 1 hour. Drain beans and reserve the cooking liquid, removing and discarding onion with garlic clove and bay leaf. Transfer beans to a large mixing bowl.

Casserole

1/2 pound thick-sliced bacon, chopped

2 ribs celery, diced

2 carrots, diced

1/2 onion, diced

salt to taste

1 teaspoon olive oil

1 pound link sausages (preferably French herb sausage), cut in half crosswise

1 pound cooked duck leg confit

1 1/2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon freshly cracked black pepper

1 teaspoon herbes de Provence (or similar herb mixture)

1 (14 ounce) can diced tomatoes

Topping

1/4 cup butter

4 cloves garlic, crushed

2 cups panko bread crumbs

1 bunch fresh parsley, finely chopped

salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

1 tablespoon olive oil

DIRECTIONS

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees F (175 degrees C).

- Cook bacon in a large, heavy Dutch oven over medium heat until lightly browned and still limp, about 5 minutes. Stir celery, carrots, and 1/2 diced onion into bacon; season with salt. Cook and stir vegetables in the hot bacon fat until tender, about 10 minutes.

- Heat 1 teaspoon olive oil in a large, heavy skillet over medium heat; brown sausage link halves and duck confit in the hot oil until browned, about 5 minutes per side.

- Season vegetable-bacon mixture with 1 1/2 teaspoon salt, cracked black pepper, and herbes de Provence; pour in diced tomatoes. Cook and stir mixture over medium heat until juice from tomatoes has nearly evaporated and any browned bits of food on the bottom of pot have dissolved, about 5 minutes. Stir mixture into beans.

- Spread half the bean mixture into the heavy Dutch oven (or traditional Cassoulet baking dish) and place duck-sausage mixture over the beans; spread remaining beans over meat layer. Pour just enough of the reserved bean liquid into pot to reach barely to the top of the beans, reserving remaining liquid. Bring bean cassoulet to a simmer on stovetop and cover Dutch oven with lid.

- Bake bean cassoulet in the preheated oven for 30 minutes.

- Melt butter in a large skillet over medium heat; add 4 crushed garlic cloves, panko crumbs, and parsley to the melted butter. Season with salt and black pepper, and drizzle 1 tablespoon olive oil over crumbs. Stir to thoroughly combine.

- Uncover cassoulet and check liquid level; mixture should still have several inches of liquid. If beans seem dry, add more of the reserved bean liquid. Spread half the crumb mixture evenly over the beans and return to oven. Cook, uncovered, for 20 minutes. There should be about 2 or 3 inches of liquid at the bottom of the pot; if mixture seems dry, add more reserved bean mixture. Sprinkle remaining half the bread crumb mixture over cassoulet.

- Turn oven heat to 375 degrees F (190 degrees C) and bake cassoulet, uncovered, until crumb topping is crisp, edges are bubbling, and the bubbles are slow and sticky, 20 to 25 more minutes. Serve beans on individual plates and top each serving with a piece of duck and several sausage pieces.

Up next: Appellations and Winemakers (Part 3)

1 thought on “Traditional Southwest France: Malbec and Tannat”